Fossil Glen Nature Reserve

Tetewatón:nis “Regrowing, or Growing Again”

Miskwaabikakik

Location

GPS Coordinates

As you travel up the Saugeen (Bruce) Peninsula, you are within the homelands of the Saugeen Anishinaabek and the Saugeen Ojibway Nation (SON). The Bruce trail at Copperkettle is located on the Sydenham section of the Niagara Escarpment, in Grey County, and runs through a 27.5-hectaire nature reserve called Fossil Glen. The Bruce Trail Conservancy purchased the property in 2015, and has since managed it for conservation.

Here, the Niagara Escarpment forms a horseshoe shaped curve, 2 km deep and 1.5 km wide, pointing in a southwesterly direction. This meander in the escarpment was carved by glaciers due to the last ice age. The center of the “horseshoe” is a lowland area sheltered on three sides by cliffs, and contains significant wetlands that receives groundwater from cold, freshwater springs. These wetlands are home to a diversity of amphibians and waterfowl.

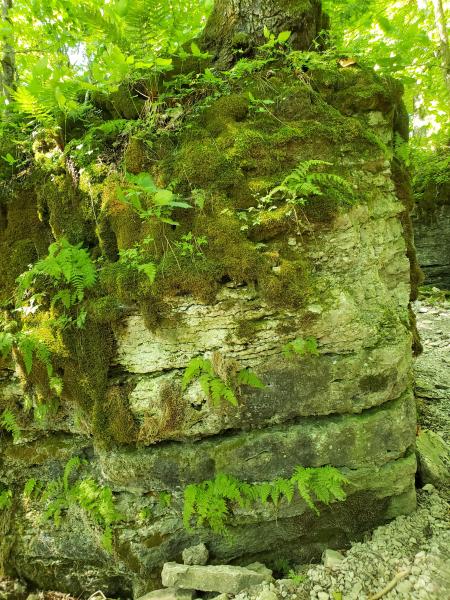

The main Bruce trail winds through forests littered with dolostone boulders, crevices and caves. The stones are often lushly covered with carpets of moss, but where the dolostone rocks are exposed, visitors can find fossils from marine species including corals and stromatolites (large colonies of microbes) from the Ordovician to Silurian periods of geologic history.

Fossil Glen hosts deciduous and mixed wood forests in various stages of succession, from young to nearing old growth. Younger forests are located close to the trail head, and are composed of dense, young sugar maple trees interspersed with ash saplings and cedar trees, and a couple of individual mature maples trees. This age structure is typical of regrowth following agricultural abandonment. The ground cover in these young forests are not very diverse, and consist of seedlings of hawthorns and canopy species, as well as sedges and dandelions. More mature forests occur further up the Bruce trail, and consist of larger sugar maples interspersed with cedar, balsam fir, ironwood, paper birch, red oak, and basswood, with the shrub layer containing saplings of these same species, as well as dogbane. These forests occur on thin soil over loose dolostone bedrock, and are accompanied by a diversity of herbaceous species such as Canada mayflower, helleborine orchids, sarsaparilla, trilliums, sedges, asters, goldenrods, ramps, and Solomon’s seal, demonstrating a range of plant and tree species that are culturally important Anishinaabe ethnobotanicals. In addition, an abundance of ferns, including northern holly fern, spinulose wood fern, and marginal wood fern, cover the forest floor.

The first human inhabitants in Grey County documented by Western archaeology were in what is described as the Paleoindian period (12,000 – 10,000 BC), a time when Indigenous cultures followed a mobile seasonal harvesting lifestyle after the retreat of glaciers in Southern Ontario. Archaeologists hypothesize that people were first active around the shorelines of Georgian Bay, Lake Huron, and gradually moved their villages inland over time. There is a paucity of archaeological documentation of Paleoindian cultures in Grey and Bruce Counties compared with the rest of southern Ontario, likely due to lack of research and unstable lake water levels throughout the Paleoindian period, which may have obscured material remains. However, the artifacts that have been found, consisting of scattered stone tools, show that the peoples Indigenous to today’s Grey County during the Paleoindian period mined Collingwood chert from the nearby Beaver Valley, and used quartzite from the La Cloche mountains north of Lake Huron. Beaver Valley chert has been found as far south as Michigan, which suggests that Indigenous peoples of this time period occupied large territories and conducted travel and trade across long distances. Where there is a paucity of archaeological information in this geography, scholars should turn to listening to the oral histories of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation Anishinaabek.

Ancient lifeways here centered on an annual cycle of moving between settlement camps, following the seasonality of food and other resources. These food and lifeways continued to be practiced through the Archaic (6,500 BC – 700 CE), and well into the late Woodland periods (900 – 1650 CE). During the Archaic period, archaeological evidence shows that the Indigenous Algonquian peoples of the region began to mine copper from the Lake Superior region and engaged in long-distance trade with southern dwelling Iroquoian cultures. During the early and mid-Woodland periods, from 800 BC to 700 CE, archaeologists have identified cultural groups living in the Grey and Bruce area with what they call the Saugeen complex. The geographic range of this cultural group spanned, from the Saugeen (Bruce) Peninsula to the North, to the Northern shores of Lake Erie in the South, and London in the East, to just east of the Grand River, where Algonquian and Iroquoian homelands meet, to the West. Archaeological research suggests what contemporary Odawa people know: that the people of the Saugeen complex were the ancestors of the Anishinaabe Three Fires Confederacy. Anishinaabe oral history also recounts a migration of the Anishinaabe people from the East coast of what became Canada and the United States, to the place “where food grows on the water” in the ancient past. This relationship is traced through the commonalities between the Algonquian languages on the East Coast and the Great Lakes region. Oral history from the Saugeen Ojibway Nation (Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation and Saugeen First Nation) recounts their peoples living in their homelands from 7500 years ago or earlier, so the Anishinaabe oral history that tells of people migrating to the Great Lakes Region must be ancient, and perhaps also continued over long periods of time.

During the late Woodland periods (900 – 1650 CE), the Odawa peoples lived on Bruce Peninsula and the shores of Georgian Bay and continued to follow a lifestyle of moving between seasonal villages and camps. There have been clusters of archaeological finds that represent Odawa fishing and hunting camps in the vicinity of Georgian Bay and current day Owen Sound. During the time of early European contact, the Odawa participated in conflicts in alliance with the Neutral and Petun (Iroquoian peoples) against the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Following the end of the conflict through the Great Peace of 1701, which ended the Beaver Wars, the Odawa hunted Bruce and Grey counties and participated in the fur trade.

Beginning in 1836, the Saugeen Ojibway Nation entered into a series of treaties and land agreements with the British Crown. The treaties in theory opened land to European settlement in exchange for Crown protection from further encroachment by settlers and moneys from land held in trust for SON by the crown, but in practice, as in other treaty agreement places in Canada, it was interpreting as selling or surrenduring the land to settlers as property, to “keep the peace” so that those settlers would not engage in conflict with SON. The Treaties of the Saugeen (Bruce) Peninsula are 45 ½ (signed in 1836), 67 (signed in 1851), 72 (signed in 1854), 82 (signed in 1857), and 93 (signed in 1861), and we recommend that learners familiarize themselves with SON interpretation of the agreements encoded in these treaties. European settlers began to farm in Grey County in the 1850s, concurrent to the signing of these treaties.

A Brief History of the Saugeen Peninsula (2018) by David D. Plain.

Georgian Bay Biosphere Species at Risk Group: https://georgianbaybiosphere.com/species-at-risk/

Georgian Bay Biosphere “State of the Bay, Gnawenjigaadeng Mnidoo-gamii Protecting the Great Lake of the Spirit.” 2023.

The illustrated history of the Chippewas of Nawash (2003) by Polly Keeshig-Tobias

The Northern Bruce Peninsula Ecosystem: chapter2.indd (wildlandsleague.org)

Saugeen Ojibway Nation website: https://www.saugeenojibwaynation.ca

Saugeen Ojibway Nation nearing land settlement with Saugeen Shores:

https://london.ctvnews.ca/saugeen-ojibway-nation-nearing-land-settlement-with-saugeen-shores-1.5510481

Sydenham Nature Reserve – Bruce Trail Club: Sydenham Bruce Trail Club - Conservation

Treaty Recognition Week: In Recognition of the SON-Crown Treaties: https://brucepeninsulapress.com/2020/11/27/treaty-recognition-week-in-recognition-of-the-son-crown-treaties/

Under Siege: How the People of the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation Asserted Their Rights and Claims and Dealt with the Backlash (2005) - Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation Report to the Ipperwash Inquiry, Pages 1-13.

Welcome to the Saugeen Ojibway Nation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dv_jGZyg0Lc

| English | Latin | Kanienʼkéha | Anishinaabemowin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Ginger | Asarum canadense | tsyonehskwénrye | namepin, nmepin |

| Yellow Birch | Betula alleghaniensis | tsyotsyó:ren | wiinizik (-oog, plural) |

| White Ash | Fraxinus Americana | káneren | aagimaak, bwoyaak |

| Green Ash | Fraxinus pennsylvanica | kaneróhon | emikwaansaak, aagimaak, bwoyaak |

| Sugar Maple | Acer saccharum | wáhta’, ohwáhta | ininaatik, ininaatig (-oog, plural) |

| Balsam Fir | Abies balsamea | otshohkó:ton | zhingop |

| Wild Leeks | Allium tricoccum | o'nyónkseri | bgoji-zhi, agaagawinzh (-iig, plural), siga'gawanj, siga'gawanch |

| Spreading Dogbane | Apocynum androsaemifolium | wahseriye'tonnyà:tha, skatsí:wa'k | sasa'bikwan, ma'kwona'gicobji'bik |

| Wild Sarsaparilla | Aralia nudicaulis | tsyotere'se'kó:wa, yonekó:wa, tsyawenséhsha, otsyawénhsa | waaboos-odji-bik, waabooz jiibik |

| Wild Ginger | Asarum canadense | tsyonehskwénrye | namepin, nmepin |

| Yellow Birch | Betula alleghaniensis | tsyotsyó:ren | wiinizik (-oog, plural) |

| Paper birch | Betula papyrifera | watenakè:taron's, watenakè:taronhs | wiigwas (singular), wiigwaasaatig (plural), wiigwaasi-mitig |

| Blue Cohosh | Caulophyllum thalictroides | karhakón:ha, kahrhatakon | kwemshkiki, be'cigodji'bigak, bezhigojiibik, zhiigimewibag |

| Alternate-leaf Dogwood | Cornus alternifolia | teyotsí:tsayen | moozwemizh, moozomizh, niibiishan miskwaabiimizhiig |

| Québec Hawthorn | Crataegus submollis | ohì:kta wahyarà:ken, yotironhwentsí:yo | miinensgaawanzh |

| Broad-leaved Helleborine | Epipactis helleborine | (check this) | (check this) |

| Trout Lily | Erythronium americanum | skatsihstóhkonte | namegbagoniin |

| White Ash | Fraxinus Americana | káneren | aagimaak, bwoyaak |

| Green Ash | Fraxinus pennsylvanica | kaneróhon | emikwaansaak, aagimaak, bwoyaak |

| Sharp-lobed Hepatica | Hepatica acutiloba | kontirontá:non, karón:tanonhne | gabisan’ikeag, a'nima'sid |

| Butternut | Juglans cinerea | tyohwá:ta, kyewhá:ta, tyehá:ta, atyehwà:ta, tsiohsò:kwehs | mtigwaabaakook |

| Wild Mint | Mentha arvensis | ye’tonhkwanóhstáhkwa, ie'tonhkwanohstáhkwa', kanóhstha | namewack, aandek-bagoohnsean |

| Ironwood | Ostrya virginiana | tysoráhsa | maananohns, maananoons (-ak, plural) |

| Downy Solomon’s seal | Polygonatum pubescens | kítkit o'éta | agongseminan, agong’osiminan |

| Holly fern | Polystichum lonchitis | (check this) | (check this) |

| Black Cherry | Prunus serotina | é:ri, e:ri’kó:wa, tyotyò:ren | ookweminagaawanzh, ookweminan, ikwe'mic |

| Red Oak | Quercus rubra | karíhton | miskode-miizhmizh, mitig mewish (-iik plural) |

| Zig-zag Goldenrod | Solidago flexicaulis | otsí:nekwar niyotsi’tsyò:ten | ajidamoowaanow, waabanoominens/waabanoominensag, giizisso mashkiaki |

| Calico Aster | Symphyotrichum lateriflorum | teyonerahtawe'éhston, yotsiron’onhkóhare orón:ya | name'gosiibag |

| Dandelion | Taraxacum officinale | tekaronhyaká:nere | mindemoyanag, doodooshaaboojiibik, mindimooyenh, wezaawaaskwaneg |

| White Cedar | Thuja occidentalis | onen’takwehtèn:tshera | giizhigaa'aandak, giizhik |

| Basswood | Tilia americana | ohóhsera | wiigobiish, wiigob, wiigobiig (plural) |

| White Trillium | Trillium grandiflorum | tsyonatsyakén:ra niyotsi’tsyò:ten, tsyoná:tsik, áhsen niioneráhtonte | ininiiwindibiigegan, baashkindjibgwaan, baushkindjibgwaun, ini'niwin'digige'gun |