Background: The Greenbelt Indigenous Botanical Survey and Field Guide project arose from years of community-based work and conversations on cultural resurgence, and the critical need for pedagogy that supports transmission of Indigenous Environmental Knowledges. The project stems from a primary Haudenosaunee philosophy and ethic that teaches about human responsibilities within the natural world: in order to be able to be caretakers of mother earth, human beings must be able to recognize, name and speak with all of the species and life forms, without which we would not exist. Acknowledging our relationality is a practice of gratitude that identifies interconnection and balance in creation. The wisdom to acknowledge this relationality is the dedication in the practice of the foundational environmental philosophy of the Haudenosaunee – The Words that Come Before All Else, also called the Thanksgiving Address, or Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen. Haudenosaunee culture-bearers teach that our responsibilities as humans are to return to this spiritual practice of gratitude every day, to communicate with Creation and identify how all of life is intricately connected and yet delicately balanced, to ground ourselves in the humility that we have everything that we need, if we but take the steps to implement care in our roles and responsibilities in creation. The Thanksgiving Address identifies all the entities in Creation that make life possible, from the Earth to the Sky – including the trees and plants, such as the medicine plants and food plants.

Through research and professional work in Indigenous environmental conservation, education, restoration, and current conversations in Indigenous environmental studies, Dr. Jessica Dolan came to learn the need for culturally-grounded pedagogical resources for restoring Indigenous knowledges of ethnobotany. The legacies of residential schooling, forced migration, urbanization, and the effects of acculturative policies on rural and urban Indigenous communities created inter-generational disruptions in transmission of traditional environmental knowledge. And yet, for the last 20 years, there has been an Indigenous resurgence across Turtle Island, wherein communities have been restoring all forms of knowledge, culture, governance, language, and kinship in their societies. In 2016, Tim Johnson and Larry McDermott of Plenty Canada, began to discuss with Jessica her idea to research and write a Haudenosaunee ethnobotanical field guide that would be an accessible, and culturally-grounded resource to support land-based learning programs, language programs, and environmental governance that people were building across their communities. At the same time, Plenty Canada began creating The Great Niagara Escarpment Indigenous Cultural Map to reanimate Indigenous landscapes and stories along the UNESCO designated Niagara Escarpment Biosphere.

Beginning in 2020, Tim Johnson, Larry McDermott, and Jessica Dolan built a research team with Robin Roth, Faisal Moola, and Mia Yu Zhao Ni of University of Guelph; Tehahenteh Frank Miller and Alyssa General of Six Nations of the Grand River; and Brian Peltier of Wiikwemkoong Unceded Anishinaabek Territory, to combine projects to create a digital cultural atlas and printed field guide that would recover and convey Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek relationships with plants and trees on the landscapes of Southern Ontario.

Our Project Goals:

To research historical and contemporary culturally-significant plants and trees, used for food, medicine, craft, and utility, among Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe in Southern Ontario.

To create a digital atlas of these ethnobotanical vegetative communities, that will be an accessible learning tool, to uplift the invaluable nature of people-plant relationships there.

To write a user-friendly printed field guide as a land-based and language learning tool for restoring and regenerating the Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) of Indigenous harvesting rights and responsibilities.

To contribute to Indigenous environmental management and in-situ conservation efforts, by creating tools that can be used by Indigenous environment departments and policy-makers, as bridges for learning and implementing cross-cultural environmental planning. This supports nation-to-nation relationships between First Nations and settler governments.

Our Intended Audiences: Much of our area of study is urban or peri-urban, and yet the populations of Indigenous peoples who live throughout the areas included within and adjacent to the Greenbelt are large and diverse. One of the broader goals of our research is to create resources that both show and advocate for Indigenous-led conservation and Indigenous governance. There is a global stereotype that rural and remote Indigenous knowledges are more “real” or “authentic.” What we show here is the uninterrupted nature of relationships with land and place that persist throughout Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek homelands, despite rapid environmental and social changes, including urbanization, experienced by all. The urban or peri-urban nature of First Nations should not undermine their inalienable rights to their homelands, and the constitutional agreements of nation-to-nation governance that must be honoured by the federal government. These relationships, and the richness contained in Indigenous knowledges and relationships with their homelands can only be made plain through experiential learning.

Our project is supported by the Greenbelt Foundation, which stewards the areas around the Western end of Lake Ontario, up the Niagara Escarpment, and into the Oak Ridges Moraine (https://www.greenbelt.ca/). As such, our geographic area of study is delineated according to the areas of the Greenbelt. Our Indigenous operational home is Plenty Canada. Our academic home is the University of Guelph Conservation Through Reconciliation Partnership (https://conservation-reconciliation.ca/). The CRP team is dedicated to mobilizing Indigenous conservation across Canada, through creating ethical spaces wherein researchers and knowledge holders work together to implement Two-Eyed Seeing to create Indigenous protected and conserved areas. Therefore, our intended audiences are:

Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek community members and educators, who are involved in language revitalization, environmental governance, protection and restoration, and education;

Policy makers, developers, environmental managers and conservationists throughout Southern Ontario and beyond;

Visitors to the Greenbelt trails who intend to use this Indigenous Botanical Survey to learn in place;

And – you!

Structure and Methodologies of the Project: We assembled our team to be cross-cultural and intergenerational, guided by the practical insights and needs of Mohawk and Anishinaabe environment departments, language and culture teachers. We choose to work this way, because our foremost commitment is to create pedagogical materials to support Indigenous language, environmental caretaking, and land-based learning programs. We are enacting these values through prioritizing:

Intergenerational knowledge regeneration, data repatriation and reclamation;

Accountability to Indigenous communities whose homeland and cultures we are studying, by taking direction from Indigenous team members;

Horizontal leadership, generational and gender balance, and inclusivity of multiple experiential perspectives; and

Language revitalization of Kanyen'kéha and Anishinaabemowin plant names and science through the processes and contents of the publications.

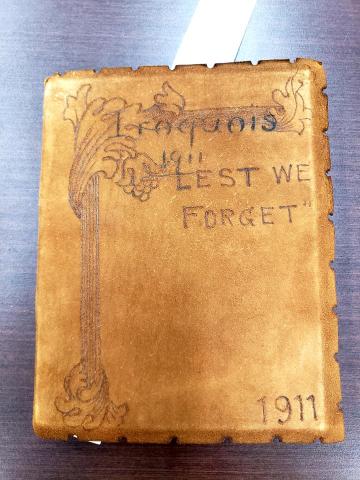

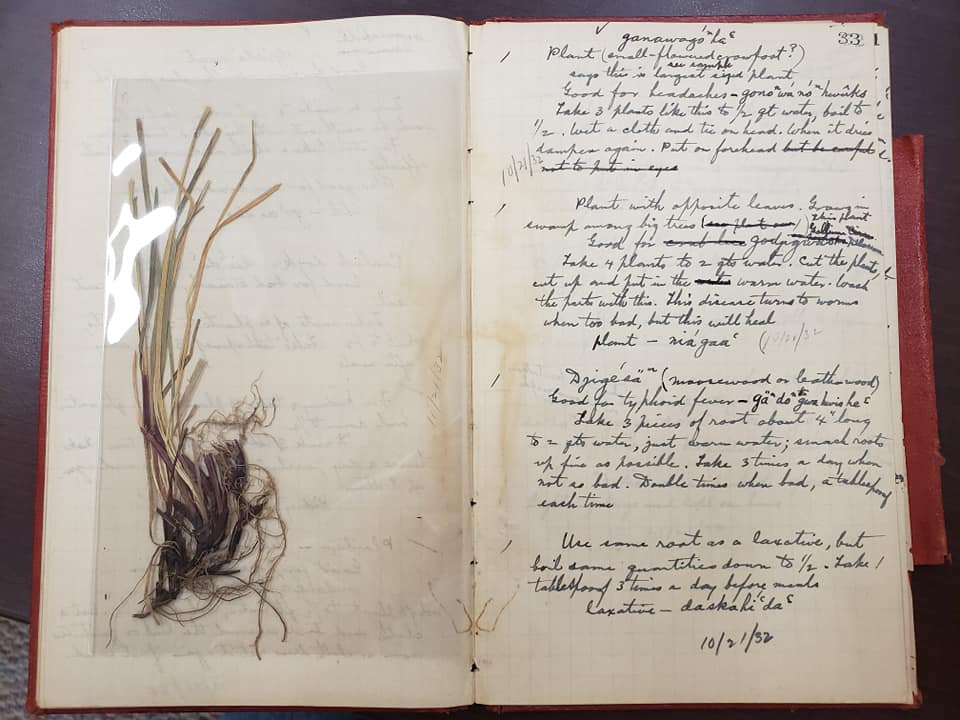

Cultural Research Methods: The cultural and ethnobotanical research on this project are designed by incorporating methods from ethnobiology, Indigenous research in museums and archives, and applied Indigenous environmental studies. Dr. Jessica Dolan first created a baseline historical dataset of from the archives of the Frederick Wilkerson Waugh collections at the Canada Museum of History, found here: https://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/tresors/ethno/etp0900e.html. The Canadian Geologic Survey hired F. W. Waugh to research lifeways of Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek communities between 1911 and 1924. His archives at the museum are extensive; F. W. Waugh collected thousands of pages of written notes from Haudenosaunee, Anishinaabek, Innu, Inuit, and other Indigenous peoples, along with taking photographic portraits of them, and purchasing artifacts. His notebooks are full of sketches of the Indigenous sciences and knowledge systems he was studying, as well as pressed plant leaves, and notes in the Indigenous languages he was studying.

Knowledge contained in Mr. Waugh’s archive derives from the ancestors of current generations of people at Six Nations of the Grand River, Wiikwemkoong, and other First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities. The family surnames are the same. Indigenous colleagues advised Dr. Dolan on the kinds of cultural information that would be appropriate to research and include in the publication that are the outcomes of this project. As part of our team value of cultural repatriation, Dr. Dolan sent copies of roughly 1,000 pages of digital files to several dozen colleagues who come from Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek communities. This is their family knowledge that was disrupted and denied through Canadian and American acculturation and termination policies. These methods of sourcing historical information from archival ethnological records at colonial institutions, and reinterpreting them within contemporary contexts, to restore language and knowledge transmission are part of a growing field of Indigenous archival restorative research.

Dr. Dolan read through the notebooks and created metadata charts on Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek ethnobotany to organize all the plant knowledge contained in the archival and published resources. The charts are organized by English names on the Y-Axis, and by Latin and Indigenous nomenclature, conservation status, habitat, ground truth status, and source of knowledge on the X-Axis. She paired historical data with contemporary datasets to demonstrate a diachronic nature of knowledge transmission and persistence. Contemporary data sources include her notes from fieldwork over the years for Akwesasne, Onondaga Nation, and Six Nations, as well as many community-based publications, projects, language charts, and dissertations. With these data that demonstrate knowledge transmission from over 100 years ago, if not far earlier, and with Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek knowledges side-by-side, we uplift and celebrate the similarities, differences, and richness of Indigenous living heritage on the landscapes of Southern Ontario.

Indigenous Data Sovereignty doctoral student Marina Johnson-Zafiris, who is of the Wolf Clan from Akwesasne, describes data re/matriation in our project as follows:

“Data reclamation is the process of turning to extracted knowledge within historic institutional archives and placing it back into Indigenous (in our case Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek) orature in order allow these plant data facets to exist as living, breathing subject matters. This allows for the plant data to be storied rather than simply stored. The orature acts as the framework for our digital architectures. In our construction of the digital atlas and field guide, our Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek partners have full access and regulatory stewardship of the ethnobotanical data that lives in these frameworks – promoting the self-determination and empowerment of Indigenous communities in the collection, management, and use of their own data.”

While carrying out the archival components of the ethnobotanical research, Dr. Dolan built an Indigenous Advisory Team, who worked with her to identify the plant names in Kanyen'kéha (Mohawk language) and Anishinaabemowin. Together, we worked to ensure a consistent orthography of those plant names; provide translations of those names into English – which often contain valuable information about the ecology and morphology of the plant or relationship between the people and the plant; carefully consider the cultural verity, ethics, and appropriateness of the contents; to shape the framework and orientation of the cultural components of the digital survey and printed field guide; and advised on uses of plants and trees. This team consists of Mohawk language and culture teachers Tehahenteh Frank Miller and Alyssa General who are from Six Nations of the Grand River, and Odawa culture-bearer Brian Peltier from Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory. In 2023, Brian Peltier was no longer able to work on the project, so Ojibwe language teacher Robert Irvine Ryckman joined in August of 2023, to fill in the missing Anishinaabemowin plant and place names.

Biological Research Methods: Biological research and field survey methods on this project were built by Mia Yu Zhao Ni with the guidance of her graduate advisors Faisal Moola and plant biologist Liette Vasseur. She created a survey of ethnobotanical plant communities to reflect phytosociological and biocultural understandings of plant ecology in the Greenbelt. Phytosociology is a Western scientific field of study focused on classifying and explaining plant species occurrence over space and time. Because vegetation is so important to ecosystem structure and function, plant communities form the basic unit of many land classification systems employed in planning and resource management.

Extant plant communities reflect diverse processes such as disturbance history, environmental conditions, dispersal and inter and intra-species interactions. Human activity is an important component of these above-mentioned processes, and reflects human relationships with plants. Indigenous Knowledge Systems embed understandings of plant community ecology as well as Indigenous land management. Indigenous land management was formative for vegetation composition across North America. European colonization destabilized Indigenous peoples’ abilities to steward their homelands due to imposed colonial land management regimes such as logging, agricultural conversion and urbanization. Although this produced environmental changes that shifted vegetation compositions, legacies of Indigenous land management endure in Indigenous Knowledge Systems, and are still reflected in current vegetation composition on the landscapes of the Greenbelt and Southern Ontario, as elsewhere.

Mia Yu Zhao Ni conducted phytosociological plant community surveys in areas of historic and contemporary significance to Indigenous peoples in service of demonstrating the cultural knowledge of people-plant relationships within the Greenbelt and regenerating and restoring Indigenous environmental knowledge systems. She focused on areas within the Greenbelt that are along historic Indigenous trails, which were complex systems of footpaths and waterways that facilitated movement, connectivity and livelihood, and were focal areas for Indigenous management of the landscape. Along these trails, she located sites at historic villages and resource gathering areas. Additionally, areas of contemporary significance were identified by Indigenous teachers. In total, and with field research assistance from David Botcherby and Joy Amyotte, we surveyed 69 plots across 23 sites. At each plot, we identified and recorded the cover of all plant species.

Mia Yu Zhao Ni, David Botcherby, and Joy Amyotte collected 1,204 herbarium voucher specimens of plants they surveyed, creating a permanent record of their occurrence. Those herbarium voucher specimens are accessioned at the University of Guelph Herbarium. They also scanned those specimens, for visual representations as learning resources in the botanical survey and field guide.

The field survey generated a list of 452 vascular plant species. Cross-referencing with the combined Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek ethnobotany datasets, we identified 233 species of ethnobotanical significance found within the landscapes of the Greenbelt. Our results show the ethnobotanical significance of plant communities within the Greenbelt geographic range, but do not reflect all of the culturally significant plants in southern Ontario nor all of Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek ethnobotany. However, the presence of 233 ethnobotanical species of historic and contemporary cultural importance does demonstrate the biocultural richness and dynamism of Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek living relationships with plants and trees in the urban, peri-urban, and rural environments of the Greenbelt.

What you will find in this survey and the field guide: Each plant profile included in the Greenbelt Indigenous Botanical Survey includes species names in Latin, English, Kanyen'kéha, and Anishinaabemowin, and translations of the Indigenous names into English. Botanical species are cross-referenced according to plant types, ethnobotanical uses, and habitat types, so learners will be able to understand where to go to learn the plants, and the different kinds of vegetative communities they form. Botanical photography will help learners gain knowledge of defining characteristics of each species, and historical and contemporary photographs will provide learning aids for species’ cultural significance.

Conclusion: Our research of plant and tree relatives is shaped by cultural knowledge and responsibilities embedded in Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek relationships with them. We are using Western science in service of regenerating and restoring Indigenous environmental knowledges by investigating the legacies of Indigenous land management within the plant communities of the Greenbelt, and combining that with oral historical and ethnographic insights into cultural legacies of relationship with plants and trees. These choices serve our greater goals of creating publications that will serve Indigenous communities first, and the general public second. The survey and field guide are intended to support Indigenous nations to implement Indigenous-led conservation, language and environmental education, nation-to-nation co-governance, and treaty relationships with settler governments and citizens. We hope this project will help tell the story of enduring and beautiful Indigenous relationships with their homelands in Southern Ontario, by educating the public about the timeless and living nature of Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek relationships with plants and trees.