Names and Their Meanings

Sassafras - Sassafras albidum

Sassafras

Description

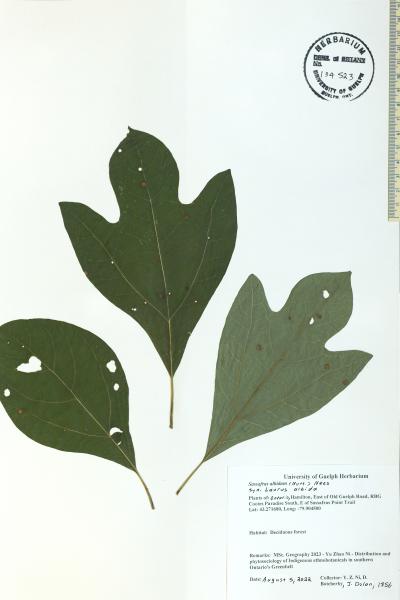

Sassafras is a moderately fast growing, deciduous, aromatic tree that is native to Eastern North America, and has a growth habit of a small tree in the north of its range, and a tree in the south. Sassafras has three distinctive leaf shapes: ovate (spoon-shaped), mitten-shaped, and three-lobed (fork-shaped), which grow on long stems. Its leaves are bright green, silky when young, with the underside of each paler than the top, or whitish – which is the meaning of the Latin epithet “albidum.” The fall foliage of Sassafras turns bright orange and yellow. Like other members of the Lauraceae (laurel) family, all parts of this tree are fragrant, including the wood, leaves and young bark. Its fragrance is the reason for the common names of cinnamon-wood and smelling tree, and the Mohawk name wenhnákeras (“smelly thing”). Sassafras grows on moist, well-drained sandy loams in open woodlands that provide light shade and regular irrigation. It frequently grows in abandoned fields, groves, near rivers or water bodies, urban locations, and along fences and roadsides, where it is important to wildlife as a browse plant. Sassafras has a large taproot that forms suckers, and can grow in thickets formed by underground runners from parent trees.

Conservation Status

S4 (Apparently Secure) in Ontario; S5 (Secure) in New York

USES

Sassafras is an ancient and consistent medicine among the Indigenous peoples whose homelands comprise its habitat. Historical Haudenosaunee uses of Sassafras as recorded by Frederick Wilkerson Waugh at Six Nations of the Grand River in 1911 and 1912 include a source of yellow or orange dye, and tea as a medicine for a “bleeding cough/ consumption” (tuberculosis). Sassafras is also mentioned as a beverage, as a tea. At Onondaga Nation, Sassafras is collected and made into tea as a spring tonic, to clean the blood, and especially for “balancing sugar” if one is diabetic. Akwesasne botanist Peggy Pyke-Thompson writes in her Traditional Medicines of Akwesasne that, “Sassafras serves as an example of how the Iroquois contributed to the introduction of medicines into Europe."

Throughout the areas where Sassafras overlaps with Sugar Maple, an Indigenous medicinal tradition is to make it into a tea during the springtime while the sap is boiling, as a tonic. One would boil sap for a little while – not until syrup – and then add the roots and boil a bit longer. Fernald and Kinsey also note that the bark of the roots were dried and kept as a flavorful chew. That same bark could be grated into boiling sugar and made into a condiment. Young leaves, stems, and pith are mucilaginous, and are cut, dried and powdered to make the flavorful thickener of gumbo in the south. This powder can be put into a salt shaker and used as a condiment in that way, too. The soft, brittle, lightweight wood has had limited commercial value, but oil of sassafras is extracted from root bark for the perfume industry. Scott Herron has also written that Sassafras is considered medicinal among the Anishinaabe who he worked with in the 1990s.

European settlers and “explorers” were immediately taken with this small tree, and espoused its many virtues. This might be because Sassafras has such unique, varied leaf shapes and a distinct smell, it is easy to recognize. Samuel de Champlain learned about Sassafras during his voyage to what later became Québec, writing about it in 1606, along with red cedar, oaks, ashes, beeches, chestnuts, and other nut trees. John Smith of Virginia noted in his journal that traders and settlers immediately began to export Sassafras to England, from Massachusetts and Virginia colonies, beginning in 1602. It is important to know that these European settlers and businessmen learned about plant and tree species from Indigenous peoples. A half century later in 1656-58, Frère Le Jeune wrote from Onondaga that the powdered leaves of Sassafras healed wounds, and the roots made beautiful colors of scarlet, green, yellow, and orange dyes, more brilliant than European dyes. Early reports from explorers, Jesuits, herbalists and traders such as these, listed Sassafras tea as useful for treatment of fever, ague (which is a Malaria-like fever with lots of chills), syphilis, rheumatism, scurvy, dropsy. Large quantities of Sassafras were exported to Europe during the first two centuries of European colonization and trade in North America.